Klevius fears religiously edited humans more than "gene-edited superhumans"

Klevius wonders what difference there could possibly be between evil aliens from "outer space" who camouflage as humans and then attacks us - or humans who do the same, and in both cases based on reasoning that is completely foreigb for us. It's in this context the negative Human Rights stand out as the only true ideological safety net.

When Saudi islamofascists use a consulate Saudi territory to sharia behead an other Saudi muslim for "disrespecting" the Saudi dictator Mohammad Salman, this behavior is completely alien for the civilized humankind.

We've got loads of "gen-edited superhumans" already. Just make your pick. Is it Albert Einstein, Lionel Messi - or Peter Klevius? Or is it Mary Wollstonecraft, Marta da Silva - or Ayaan Hirsi Ali? The assessment of what is super is entirely yours. And what about "superhumans who would kill us all" - are they humans? And are we "superhumans" compared to those hunter-gatherers our way of life has killed off? Klevius recommends the last chapter in his 1992 book Demand for Resources. It's called Khoe, San and Bantu.

Stephen Hawking: Why are we here?

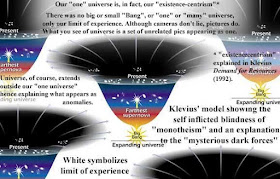

Peter Klevius: We are here because we can ask why we are here. The alternative would mean a strange state of "not being" in a "nothing" surrounded by something else. Although many people talk a lot about "nothing" they don't have a clue about what they mean by that (Klevius 1992).

Stephen Hawking: Will we survive?

Peter Klevius: Who are "we"? Did the Neanderthals survive? The only thing we can have in common as humans is the axiomatic idea about Human Rights. And apart from being axiomatic, this humankind may include individuals who have absolutely nothing else in common. "Human" is a human invention protected (Klevius 1992).

Stephen Hawking: Will technology save or destroy us?

Peter Klevius: Again, who are "us". Which non-human should we ask (Klevius 1992)?

Stephen Hawking: Will we blossom in the future?

Peter Klevius: Certainly, just as we blossom now. "Blossoming" takes its fertilizer from the miserable past (Klevius 1992).

For those who don't understand Klevius short answers, here's a longer version (extracted from Klevius 1992):

There's no "real world" outside your experience. It is your experience*.

* The naive argument that "of course the stone is there when I leave" is corrected in the chapter Existencecentrism in Demand for Resources (Klevius 1992:21-22), and to prove adaptation (i.e. not "mind") Klevius conducted the ultimate experiment, also in Demand for Resources (Klevius 1992:31-33, ISBN 9173288411):A critique of Habermas' dichotomy observing/understanding.

Observing a stone = perception understood by the viewer

I observe a stone = utterance that is intelligible for an other person

Although I assume that Habermas would consider the latter example communication because of an allusion (via the language) to the former, I would argue that this "extension" of the meaning of the utterance cannot be demonstrated as being essentially different from the original observation/understanding. Consequently there exists no "abstract" meaning of symbols, which fact of course eliminates the symbol itself. The print color/waves (sound or light etc) of the word "stone" does not differ from the corresponding ones of a real or a fake (e.g. papier maché) stone.

The dichotomy observation/understanding hence cannot be upheld because there does not exist a theoretically defendable difference. What is usually expressed in language games as understanding is a historical - and often hierarchical - aspect of a particular phenomenon/association. Thus it is not surprising that Carl Popper and John C. Eccles tend to use culture-evolutionary interpretations to make pre-civilized human cultures fit in Popper´s World 1 to World 3 system of intellectual transition.

If one cannot observe something without understanding it, all our experiences are illusions because of the eternal string of corrections made by later experience. What seems to be true at a particular moment may turn out to be something else in the next, and what we call understanding is merely retrospection.

The conventional way of grasping the connection between sensory input and behavioral output can be described as observation, i.e. as sensory stimulation followed by understanding. The understanding that it is a stone, for example, follows the observation of a stone. This understanding might in turn produce behavior such as verbal information. To do these simple tasks, however, the observer has to be equipped with some kind of "knowledge," i.e., shared experience that makes him/her culturally competent to "understand" and communicate. This understanding includes the cultural heritage embedded in the very concept of a stone, i.e.it's a prerequsite for observation. As a consequence it's not meaningful to separate observation and understanding..

Everything is adaptation - even the playing with language.

Humankind as well as individual humans are always trapped in existencecentrism (see Klevius 1992:21-22, ISBN 9173288411) meaning that the only step possible to enter metaphysics is this step backwards into the realization of the relativity of being "human".

As Klevius has said in public since 1992, the human condition (individual and collective existencecentrism) excludes every other assessment of what it means to be human. However, scientists and other thinkers often miss this point, hence causing a category fallacy.

What could possibly define the qualifications of being a human? Not a single positive definition suffices. Which leaves us with the negative and axiomatic ones:

1 The axiomatic agreement on who counts as a human.

2 The negative Human Right not to be imposed segregation affecting rights.

Understanding existencecentrism is compulsory when debating the human condition because only then one can distinguish between what can be said about humans.

When Searle says his car or calculator aren't in the business of understanding he makes the biggest possible category mistake. In fact so big so he (hopefully) must have understood it himself, which fact leaves one to think he's talking like a politician.

What business? The business of being stupid! No, machines can't do that. If, according to Searle, machines don't understand - despite machine learning - then what's the point of implying human "understanding"? Searle is incoherent in comparing human understanding with machime understanding. By doing so he presets a rule that excludes machines already before the comparison. To better understand this you may consider developing Searles machines to sophisticated AI robots without loosing the principal humanmade distinction between human and machine. Or, alternatively, if you erase that distinction then there's only a (possibly) quantiatative, not qualitative difference between Searle and his machines.

Searle's problem is that he hasn't read Klevius 'existencecentrism' chapter (1992) and clearly has lacked the capacity to come up with it himself.

Klevius wrote:

Friday, May 19, 2017

Artificial intelligence (AI), consciousness - and EMAH

Wikipedia: Artificial intelligence (AI) is intelligence exhibited by machines. In computer science, the field of AI research defines itself as the study of "intelligent agents": any device that perceives its environment and takes actions that maximize its chance of success at some goal

Peter Klevius: A shock absorber fulfills every bit of this definition - and can be digitally translated, i.e. e.g. "shock absorbed by wire", either partially or fully!

Wikipedia: As machines become increasingly capable, mental facilities once thought to require intelligence are removed from the definition. For instance, optical character recognition is no longer perceived as an example of "artificial intelligence", having become a routine technology.

Are there limits to how intelligent machines – or human-machine hybrids – can be? A superintelligence, hyperintelligence, or superhuman intelligence is a hypothetical agent that would possess intelligence far surpassing that of the brightest and most gifted human mind. ‘’Superintelligence’’ may also refer to the form or degree of intelligence possessed by such an agent.

The philosophical position that John Searle has named "strong AI" states: "The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds." Searle counters this assertion with his Chinese room argument, which asks us to look inside the computer and try to find where the "mind" might be.

Searle's thought experiment begins with this hypothetical premise: suppose that artificial intelligence research has succeeded in constructing a computer that behaves as if it understands Chinese. It takes Chinese characters as input and, by following the instructions of a computer program, produces other Chinese characters, which it presents as output.

Suppose, says Searle, that this computer performs its task so convincingly that it comfortably passes the Turing test: it convinces a human Chinese speaker that the program is itself a live Chinese speaker. To all of the questions that the person asks, it makes appropriate responses, such that any Chinese speaker would be convinced that they are talking to another Chinese-speaking human being.

Searle then supposes that he is in a closed room and has a book with an English version of the computer program, along with sufficient paper, pencils, erasers, and filing cabinets. Searle could receive Chinese characters through a slot in the door, process them according to the program's instructions, and produce Chinese characters as output. If the computer had passed the Turing test this way, it follows, says Searle, that he would do so as well, simply by running the program manually.

Searle asserts that there is no essential difference between the roles of the computer and himself in the experiment. Each simply follows a program, step-by-step, producing a behavior which is then interpreted as demonstrating intelligent conversation. However, Searle would not be able to understand the conversation. ("I don't speak a word of Chinese",he points out.) Therefore, he argues, it follows that the computer would not be able to understand the conversation either.

Searle argues that, without "understanding" (or "intentionality"), we cannot describe what the machine is doing as "thinking" and, since it does not think, it does not have a "mind" in anything like the normal sense of the word. Therefore, he concludes that "strong AI" is false.

Peter Klevius: Nonsense! 'Intentionality' is an illusion. There's no "gap" between input and output where 'intentionality' could be squeezed in. Moreover, if Searle believes in 'intentionality' he can't refute 'the free will' either. The machine could also be understood by the Chinese speakers without "understanding" - only fulfilling the Turing criterion. There is no 'understanding' or consciousness', other than the usage of these terms.

Wikipedia: No one would think of saying, for example, "Having a hand is just being disposed to certain sorts of behavior such as grasping" (manual behaviorism), or "Hands can be defined entirely in terms of their causes and effects" (manual functionalism), or "For a system to have a hand is just for it to be in a certain computer state with the right sorts of inputs and outputs" (manual Turing machine functionalism), or "Saying that a system has hands is just adopting a certain stance toward it" (the manual stance). (p. 263)

Searle argues that philosophy has been trapped by a false dichotomy: that, on the one hand, the world consists of nothing but objective particles in fields of force, but that yet, on the other hand, consciousness is clearly a subjective first-person experience.

Searle says simply that both are true: consciousness is a real subjective experience, caused by the physical processes of the brain. (A view which he suggests might be called biological naturalism.)

Ontological subjectivity

Searle has argued[48] that critics like Daniel Dennett, who (he claims) insist that discussing subjectivity is unscientific because science presupposes objectivity, are making a category error. Perhaps the goal of science is to establish and validate statements which are epistemically objective, (i.e., whose truth can be discovered and evaluated by any interested party), but are not necessarily ontologically objective.

Searle calls any value judgment epistemically subjective. Thus, "McKinley is prettier than Everest" is "epistemically subjective", whereas "McKinley is higher than Everest" is "epistemically objective." In other words, the latter statement is evaluable (in fact, falsifiable) by an understood ('background') criterion for mountain height, like 'the summit is so many meters above sea level'. No such criteria exist for prettiness.

Beyond this distinction, Searle thinks there are certain phenomena (including all conscious experiences) that are ontologically subjective, i.e. can only exist as subjective experience. For example, although it might be subjective or objective in the epistemic sense, a doctor's note that a patient suffers from back pain is an ontologically objective claim: it counts as a medical diagnosis only because the existence of back pain is "an objective fact of medical science".[49] But the pain itself is ontologically subjective: it is only experienced by the person having it.

Searle goes on to affirm that "where consciousness is concerned, the existence of the appearance is the reality".[50] His view that the epistemic and ontological senses of objective/subjective are cleanly separable is crucial to his self-proclaimed biological naturalism.

Klevius: All of this is more or less non sense due to a balancing act (deliberate or just out of ignorance) to satisfy certain needs and wishes. To understand this you need to read Klevius and contrast it with the above:

1 Existence-centrism (Klevius 1992:21-23, ISBN 9173288411), i.e. the simple fact that there's no difference between 'reality' and 'conscious experiences'.

2 Klevius EMAH - the Even More Astonishing Hypothesis which eliminates prejudices about the mind, as well as the naive idea about "a thoughtful and subjective brain", and therefore opens up for a human brain that fits the nature it belongs to and from which it emerged. Moreover, Klevius analysis also opens up for a more truly human approach to other humans, i.e. that that's what we have in common - and only we can see it, not a non-human (Klevius 1992:36-39), which fact doesn't eliminate that we should try to cope with non-humans in a "humane" way.

The preposterous thought that "we are special" stands on two contradicting pillars:

1 We, out of our existence-centrism (read Klevius' book, Jonathan!), define what's "outside" - i.e. the foundation for making (usually just some of) us "special".

2 Only by fully accepting our existence-centrism can we drop religions and fully understand what it is to be a human together with other humans (read carefully Klevius' analysis of the negative part of the Human Rights declaration, Jonathan!).

No comments:

Post a Comment